Body temperature (BT) is a measure used as an indicator to determine whether an animal is suffering from heat stress (HS; Wilson and Crandall, 2011). BT is commonly measured in the rectum (Pearce et al., 2014), but also on the surface of the skin (Yu et al., 2010), subcutaneous (Morales et al., 2016a), ear (Morales et al., 2016b) and in internal organs (Morales et al., 2015; 2016c). Pigs have the ability to transfer heat from their internal organs to the surface in order to preserve their BT unaltered (Huynh et al., 2005) by increasing their respiratory rate (Pearce et al., 2013a, 2013b). Recent studies have shown increases of up to 200% in the respiratory rate of pigs with HS (Morales et al., 2016a, Pearce et al., 2014). In addition, the exposure of pigs to HS conditions increases their BT, regardless of the point where it is measured.

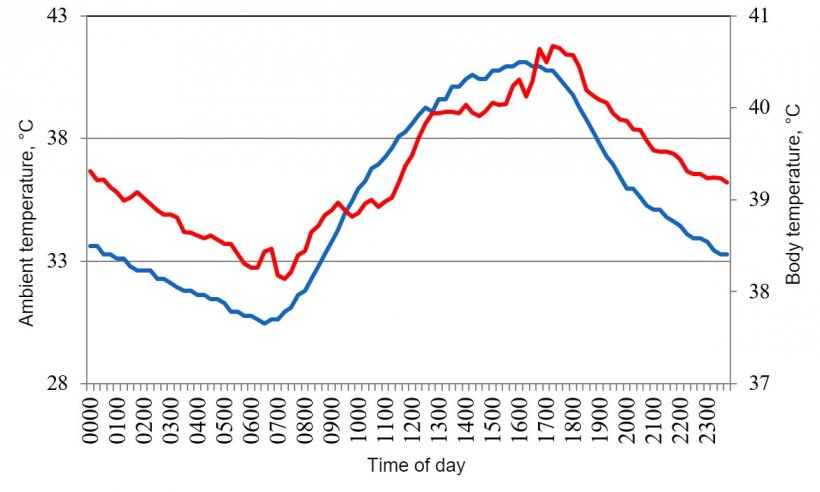

Several recent studies have shown a consistently close relationship between the environmental temperature (ET) pigs are exposed to and their BT (Morales et al., 2015; Morales et al., 2016a; 2016b). For example, Figure 1 shows the way in which the BT of pigs with HS reflects the changes in the ET during a typical summer day in arid areas (Cervantes et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Variations in body temperature (red) of pigs housed under conditions of heat stress, in response to changes in environment temperature (blue) during a typical day in the summer of 2015 in the Mexicali valley (Cervantes et al., 2017 ).

Likewise, other authors (Yu et al., 2010; Pearce et al., 2013b; 2014) observed damage in the intestinal epithelium of pigs with HS when their rectal temperature increased 1.5 ºC. This damage can affect the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and, consequently, its digestive capacity and its capacity to absorb nutrients.

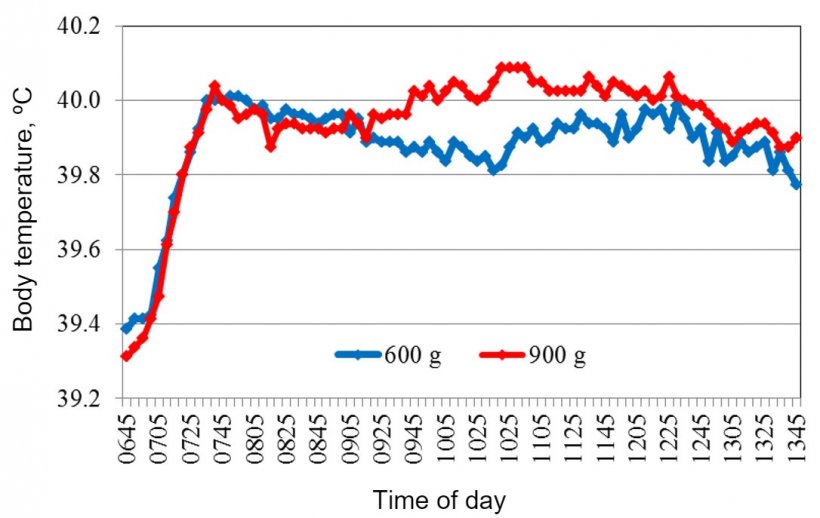

On the other hand, it is a well-known fact that the act of consuming food, together with the digestion process and the absorption/metabolism of the resulting nutrients generates additional heat. Under comfort conditions, the post-prandial BT of pigs rises slightly. In a recent study carried out in our laboratory, pigs between 50 and 60 kg live weight were housed under thermo -neutral conditions (20 ± 2 °C); thermographs were implanted in their terminal illeum, programmed to measure and record their BT every 5 min. The pigs were fed two different quantities (1.2 and 1.8 kg/d) of a typical wheat-soybean meal diet, feed twice a day (at 07:00 AM and 07:00 PM with 600 and 900 g, respectively in every meal) for 10 days. On average, as shown in Figure 2, the BT was raised between 0.6 and 0.7 ° C immediately after consuming their food ration, and remained high for approximately 5 hours after their morning meal. The initial increase in BT is attributed to the physical activity related to the action of consuming the food in addition to the typical movements of fasted animals prior to feeding. On the other hand, the sustained high BT during the 5-h post-prandial period is attributed to the chemical reactions related to the digestion and absorption of nutrients. Also, based on previous studies (Morales et al., 2016b), the standardized ileal digestibility was concluded to be around 90%. Therefore, it is estimated that most of the feed offered in the morning was digested in the small intestine, and that the resulting nutrients were absorbed during the first 5 hours after ingestion, which is consistent with the sustainment of the increase in intestinal temperature. Therefore, the increase in the intestinal temperature initiated by the physical activity of the pigs seems to be sustained by the heat produced during the digestion of the food, and the absorption and metabolism of the resulting nutrients. Even more interesting is the fact that the BT of the pigs that consumed 1.8 k / d of food was about 0.3 °C higher than that of those who received 1.2 kg / d.

Figure 2. Average body temperature recorded after feeding at 07:00 AM.

However, the effect of the consumption and digestion of feed is not consistent in pigs with HS. Figure 1 shows that their BT decreases even after consuming their evening food ration. In this study, pigs with HS were fed twice daily, at 07:00 AM and 07:00 PM. From 06:00 AM to 09:00 AM, their BT increased at a rate similar to that of the actual ET. BTs recorded between 06:00 PM and 09:00 PM, however, decreased as the ET decreased, regardless of whether the food intake occurred at 07:00 PM or not; at that time, the ET was already superior to the BT of pigs without HS. This response indicates that the effect of ET on the BT is greater than that of ingestion and digestion of food. In conclusion, because the most significant effect of HS in pigs is the marked reduction (up to 50%) in the voluntary consumption of food (Huynh et al., 2005; Morales et al., 2015), their exposure to a high ET, seems to be the main cause of the reduction in consumption, rather than the heat derived of digestion/metabolism of the food consumed.