Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae is one of the most prevalent and economically significant respiratory pathogens in the swine industry (Maes et al., 2008). Economic losses related to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae are associated with decreased average daily gain, decreased feed efficiency, and increased medication costs (Maes et al., 2018).

One of the biggest challenges with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae is that clinical signs and costs can be variable. This variability is primarily due to the stability and shedding status of the sow herd. If the herd is unstable, it results in sows shedding high numbers to piglets, which in turn will result in more severe clinical signs and costs in the finishing phase of production (Fano et al., 2007).

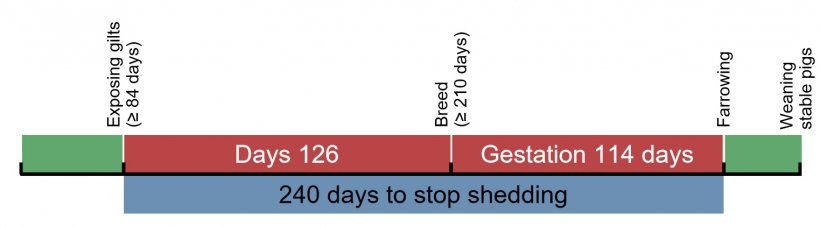

Because of this, it has resulted in the need for proper gilt acclimatization prior to entering the sow herd to maintain stability. For farms that have internal gilt multiplication, this is less of a concern since the gilts are likely to be exposed at an early age and develop good immunity. If gilts are being purchased and brought into the herd, these animals today are more likely to be negative for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. For these herds, it is critical for gilts to be exposed at an early age so they become infected, generate a good immune response, and then stabilize to shed lower numbers of organisms to piglets at the time of farrowing. With what we know about Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, it takes at least 240 days from exposure until animals develop good immunity and stop shedding (Pieters et al., 2009). To accomplish this goal, we need to work backwards 240 days from the farrowing of gilts and determine the age of exposure, which is approximately 80 days of life, depending on the age at first breeding. To do this properly, we need to receive gilts into the gilt developer at 50-80 days of age, depending on how you plan to expose the gilts to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae.

Exposure methods

Traditionally, the method of exposure was from the original sow herd when internal gilts were used. When purchased gilts are used, historically, gilts were exposed to seeder animals. The problem with seeder animals for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae is that they are relatively inefficient at exposure. The best animals to use as seeders were animals from the last group that was exposed, since they are more likely to be shedding high numbers. Recently published work from Roos et al., 2016 demonstrated that to get exposure in 30 days, it required more seeders than animals in the population, or required more time to get this done. This made this type of method less predictable and can result in inconsistent exposure and instability. If this method is used, there needs to be close diagnostic monitoring to ensure exposure is complete.

Because of the variability and inconsistency, other methods have been developed. Intratracheal inoculation has long been used as a method of challenge in research work and can be done using a lung homogenate inoculum (from the lungs of positive animals from the herd). This is very labor-intensive; it usually works best to have 3-4 people in a team to expose animals and requires well-trained staff to accomplish this properly. This can be done as either exposing all gilts or doing a seeder model with adequate numbers to get good exposure. We still need to confirm the exposure status of gilts with diagnostics at 3-6 weeks post-exposure. This method, although more labor-intensive, is more likely to generate consistent exposure of gilts entering the herd and allows us to know when this occurs.

Aerosol exposure was developed using the same lung homogenate as used for intratracheal exposure. The only difference is the delivery method: a hurricane fogger is used to aerosol the inoculum in the room for the gilts. This has been done using smaller confined spaces such as hallway loadout rooms, trailers, and just in gilt developer rooms to do the exposure. This appears to be a very effective way to do the exposure and allows for uniform exposure with less labor and concern for injuries to people and pigs. Diagnostics still need to be done to ensure that exposure has been complete at 3-4 weeks post-exposure. There is still a lot of research work needed to better understand this process and to be able to continue to fine-tune going forward for long-term best performance.

Conclusions

When proper gilt acclimatization is done, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae can be controlled, and the impact of the disease can be limited. This doesn’t eliminate the complete cost of the disease, but reduces the variability of the exposure of piglets and reduces the colonization and impact of the disease. Because of the continued cost and work involved for proper acclimatization, many producers have taken the approach to eliminate the disease as a long-term strategy.