In the previous article we looked at the first two questions in addressing a sow mortality problem: "How are sows dying?" and "Which sows are dying?" Now, we will focus on the following two questions: "When are sows dying?" and "Where on the farm are the deaths occurring?"

When are sows dying?

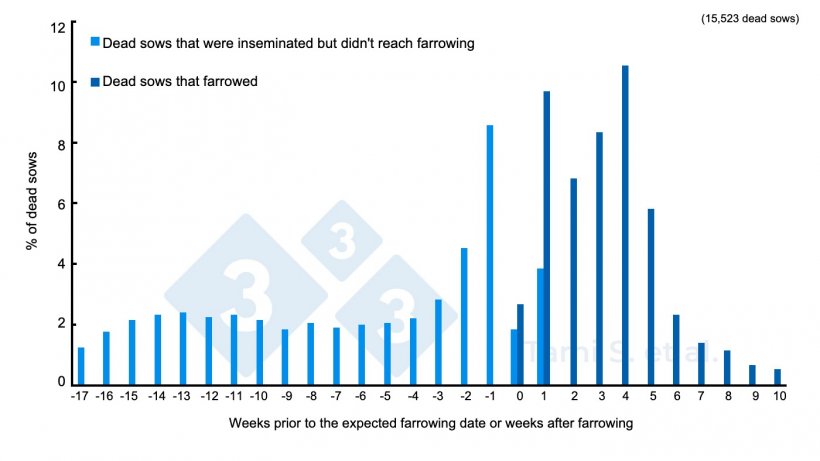

A majority of sows die around farrowing (Figure 1). We mentioned that farrowing is a time when metabolism is pushed to its limit: the sow's feed intake increases in the final phase of gestation at the same time the fetuses are reaching their largest size, all of which puts pressure on the diaphragm, limiting the sow's oxygenation capacity. When there are chronic problems associated with the lungs or heart, deaths will occur around farrowing. Pelvic organ prolapses occur mostly around the time of farrowing or after farrowing because that is when they are pushed under pressure.

When the cause of death is associated with the digestive system (torsions, ulcers, stomach ruptures) mortality is more likely to coincide during the period when sow feed intake is at the maximum, which is during lactation or the period from weaning to mating.

Figure 1. Relative frequencies (%) of dead sows, before or after farrowing, out of a total of 7,778 inseminated sows plus 7,745 farrowed sows. Source: Tami S. et al. 2017.

However, problems associated with cystitis/pyelonephritis tend to occur during the first third of gestation since this period is when urinary pH tends to be higher, facilitating bacterial proliferation.

When problems are related to lameness, they often appear during the second half of gestation: when the body weight of the sow is higher and there is more interaction between sows (if they are housed in groups as is the case in the EU ), but since these sows are pregnant, they tend to be kept until they farrow and are often culled during lactation or in the period immediately after weaning.

There are some cases in which no one time is more frequent than another. This tends to be the case on farms where the cause of death is related to acute intestinal problems: torsions, hemorrhagic bowel syndrome, or what was commonly called clostridial enterotoxemia. On these farms, the problem frequently lies in feeding routines not being respected. The sows wait for their food punctually, always at the same time and when that happens the sows are calm. There are farms where feeding schedules change depending on the tasks that need to be done. In these types of situations, sudden deaths due to digestive problems tend to be frequent and can occur at any time during the production cycle.

Where are the sows dying?

There are times when high mortality is associated with a specific area of the farm. Problems related to gases from slurry pits, for example, will always affect the same area of the farm and dead sows accumulate on specific days. In other cases, problems may arise from the electrical installation: incorrect ground connections could electrify feeders or other parts of the facilities, causing deaths due to electrocution or gastric ulcers if it intermittently affects and electrifies the feeder. In this type of situation, there may be a relationship with the age or physiological state of the sows but this would be a coincidence as a result of the area in which they were housed.

Rare cases, as their name suggests, are infrequent, but when they occur we must have all the information needed to make a diagnosis.

Naturally, investigating any case of high sow mortality should be accompanied by necropsies on the sows that are dying. Differentiating between a lameness problem derived from fractures or an infectious process is not easy without seeing the lesions, and the same applies to lung, heart, or digestive problems.

Unfortunately, too often a very small number of necropsies are performed, which creates the risk of them not representing the main problem, leading to erroneous diagnoses that will only waste time and put the sows at risk.