In this article, we will examine how climate change can indirectly decrease animals' productive and reproductive performance by affecting crop quality, altering pathogen distribution, and influencing water availability.

It directly causes stress, defined as the nonspecific physiological response to environmental demands, altering homeostasis and causing health imbalances, behavioral changes, and reduced reproductive efficiency.

This year, farms will experience a thermal shock that may be more severe than in previous years, due to the mild temperatures we have had up until a few days ago, which hasn't given the animals a chance to acclimatize more or less effectively to the heat.

This heat stress makes pigs particularly vulnerable due to their limited ability to dissipate body heat, and genetic selection for increased productivity has, in turn, reduced their heat tolerance. Heat production increases with improved technical results, and as a result, today's lines produce 30% more heat than in the 1980s. This causes the thermoneutral zone to decrease in temperature over the years at a rate of 1% per year.

Physiological effects

Heat stress occurs when the ambient temperature exceeds the pig's ability to dissipate body heat. Pigs do not have functional sweat glands; they have very small lungs relative to their body mass, and a relatively thick layer of subcutaneous fat that hinders heat dissipation; therefore, they rely on mechanisms such as convection, radiation, and evaporation to regulate their temperature.

The physiological effects of heat stress include:

- Increased respiratory rate (panting), increased heart rate.

- Peripheral vasodilation.

- Changes in posture (lying on their side, limbs stretched out).

- Muscle tremors and lethargy.

- Increased water consumption and decreased feed consumption.

Productive and reproductive impact

Heat stress has a significant impact on a pig's productivity and reproduction.

Effects on productivity include:

- Decreased weight gain (up to 3-4 kg/animal/year).

- Lower feed conversion. Poor carcass quality.

- Increased stillbirth and embryonic mortality rates.

In terms of reproductive effects, heat stress can:

- Decrease fertility in boars.

- Reduce conception rate in sows.

- Lower milk production by 20-25%

- Deteriorate sow body condition upon leaving the farrowing room, leading to returns to estrus and abortions in early gestation.

- Overall increase NPD (Non-Productive Days).

Economic consequences

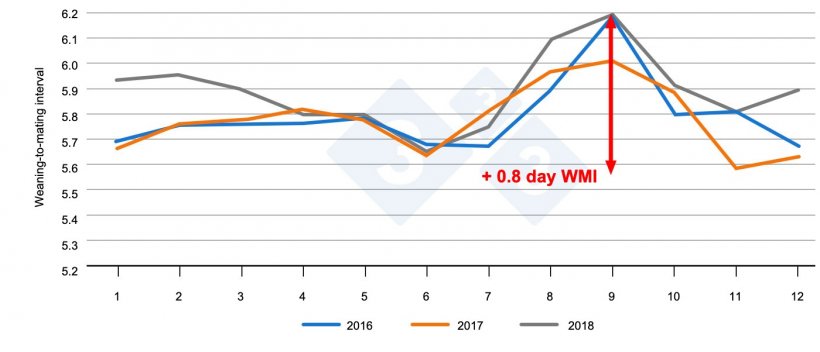

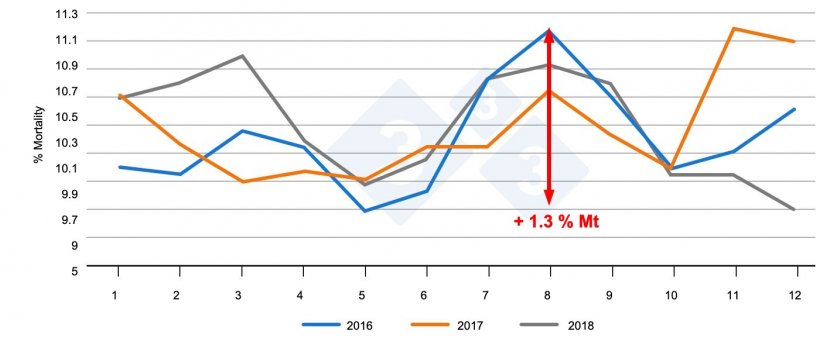

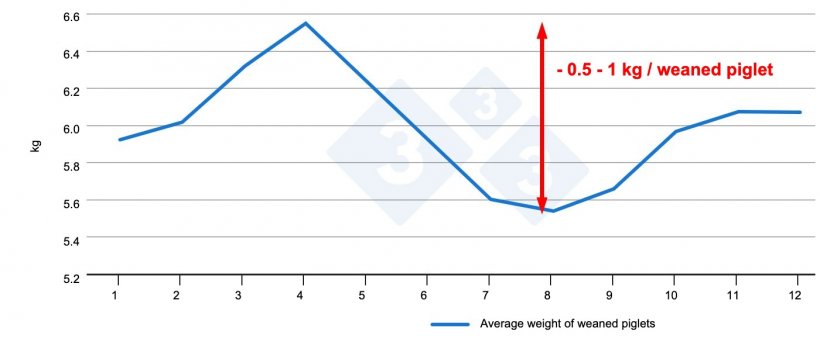

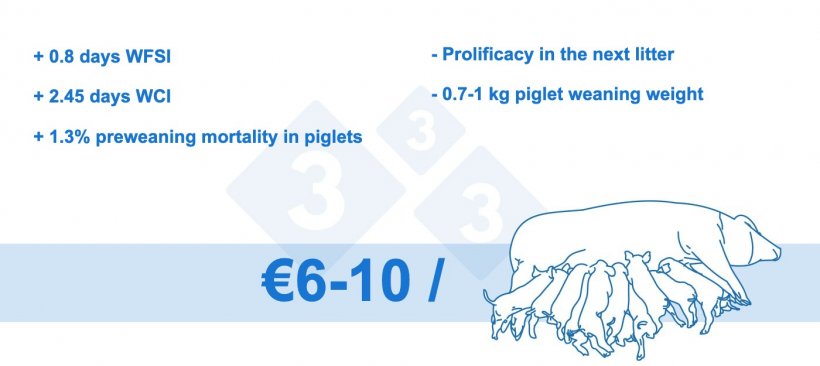

Heat stress can negatively impact sow productivity, leading to an increase of up to +0.8 non-productive days (NPD) (Figure 1), +2.45 days from weaning to first service (WFSI) (Table 1), and a rise of 1.3 piglets in pre-weaning mortality (Figure 2). It can also result in reduced prolificacy in the subsequent litter and a decrease of 0.7–1.0 kg in piglet weaning weight (Figure 3). These effects represent an economic loss of €6–10 per sow, based on our own calculations (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Weaning-to-mating interval by month of the year. Source: PigChamp Pro Europe

Table 1. Influence of farm and mating season on production results. Galé et al, 2015

| n | FR % | TB | TBA | SB | PW | NBM % | PWM % | FR | WFSI (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm | ||||||||||

| A | 52 | 82.76b | 11.6b | 10.76 | 0.84 | 9.85b | 7.28 | 8.12 | 3.95a | 11.71a |

| B | 45 | 87.64a | 12.16a | 11.18 | 1.01 | 10.29a | 8.03 | 9.15 | 0.85b | 9.23b |

| sem | 1.68 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.27 | 0.63 | |

| Mating season | ||||||||||

| Fall | 26 | 86.83a | 11.70 | 10.86 | 0.83 | 9.93 | 7.11 | 9.1 | 2.11ab | 10.23ab |

| Summer | 22 | 82.29b | 12.18 | 11.28 | 0.96 | 10.38 | 7.74 | 8.4 | 3.15a | 12.40a |

| Winter | 24 | 90.22a | 12.10 | 11.2 | 0.89 | 10.15 | 7.35 | 9.07 | 1.63b | 8.69b |

| Spring | 25 | 81.46b | 11.54 | 10.55 | 1.01 | 9.81 | 8.42 | 7.98 | 3.21a | 11.12a |

| sem | 1.50 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 1.16 | 1.43 | 0.27 | 0.91 | |

| p E < | 0.045 | 0.017 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 | |

| p EC < | 0.038 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.011 | 0.043 | |

| pE×EC | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.044 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.57 | |

| cov tl | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.65 | |

n = number of sow batches, FR % = farrowing rate, TB = total born, TBA = total born alive, SB = stillborn, PW = piglets weaned, NBM = neonatal piglet mortality (at birth), PWM = pre-weaning piglet mortality (from birth to weaning), FR = returns (return‑to‑estrus) rate, WFSI = weaning‑to‑first‑service interval, sem = standard error of the mean. Piglet mortality during lactation was studied in batches of sows in which piglets were neither removed nor adopted: 52 and 39 batches on farms A and B, respectively, and 25, 20, 24, and 22 batches in autumn, summer, winter, and spring, respectively.

Figure 2. Evolution of mortality in piglets over the months. Source: PigChamp Pro Europe

Figure 3. Piglet weaning weight by month of the year. (internal data).

Figure 4. Loss per sow obtained (internal data)

Prevention strategies

The following strategies are recommended to mitigate the effects of heat:

- Environmental management:

- Improve natural or mechanical ventilation.

- Use misters, sprinklers, or evaporative panels.

- Thermal insulation in ceilings and walls.

- Adapted nutrition:

- Provide diets with lower energy content and higher digestibility during cooler times of the day.

- Increase the number of meals for lactating sows.

- Supplement with electrolytes and antioxidants.

- Water management:

- Constant access to fresh, clean water, paying attention to water temperature.

- Increase the number of drinkers.

- Housing management:

- Reduce animal density.

- Avoid intensive handling during the hottest hours of the day.

- Genetics:

- Select animals with a more efficient thermoregulatory response

Conclusions

Heat stress in pigs is a major challenge that requires the implementation of effective management and prevention strategies. Understanding the physiological, productive, and reproductive effects of heat stress, as well as its economic consequences, is essential to ensuring animal welfare and profitability in pig production.

With this in mind, combinations of functional additives aimed at reducing the negative effects of heat stress from a nutritional perspective, reducing reproductive problems in sows, and improving performance in finishing can be helpful in addition to all of the management guidelines mentioned above.