Meat potential is determined by two key factors, one is genetics and the other is the ‘environmental conditions’ of the uterine environment. It is the latter factor which will be discussed here and will focus on the major controller of the uterine environment and that is the mother’s nutrition. The concept that prenatal conditions (particularly nutrition) can have long lasting effects into adulthood is not new. The concept is sometimes referred to as ‘foetal programming’ and has led to the idea that many postnatal growth problems or diseases in adulthood can be traced back to inappropriate foetal development. To understand how this works in terms of muscle growth and meat output, it is first necessary to understand how muscle develops in the foetus.

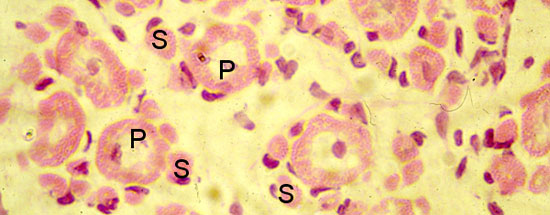

Muscle develops from cells called myoblasts which divide rapidly in the developing foetus. Between 30-50 days gestation in the pig many of these cells line up and fuse to form long primary muscle fibres. This is the first wave of muscle fibre formation. Later, between 50-80 days gestation, more myoblasts line up on the surface of the primary fibres to form a larger population of small secondary muscle fibres (see fig. 1). In the pig, around 30 secondary muscle fibres form around each primary muscle fibre. Based on the findings from a number of research papers it appears that the number of secondary muscle fibres which form can be influenced by the level of maternal nutrition. Low maternal feed levels cause a reduction in muscle fibre numbers, whereas enhanced maternal nutrition resulted in a higher number of muscle fibres in specific muscles. In one experiment pregnant sows were given double food rations between 20-50 or 25-80 days gestation, and this resulted in significantly more muscle fibres in the offspring. Interestingly it appeared that the pigs at the lower birth weight end showed the most improvement, ie intralitter variation in both muscle fibre number and birth weight was reduced.

Figure 1. Shows a microscopic cross-section of muscle tissue taken from a pig fetus during the second half of gestation. P = Primary muscle fibre; S = Secondary muscle fibre. By the time of birth primary and secondary fibres will be of similar size.

But why then is muscle fibre number at birth important? It is important because no new muscle fibres can be added after birth and because total muscle fibre number in muscles has been shown to be positively correlated with a number of important meat and growth parameters. The offspring from the supplemented mothers outlined above grew 10% faster and 8% more efficiently than offspring from mothers fed a normal ration throughout gestation. Other studies have also shown that high fibre number correlates with higher lean meat yield, lower back fat levels and, in some studies, with better meat quality.

Although the studies outlined, and other studies on a range of animal species, have shown the importance of extra feed rations given to pregnant mothers in early and mid gestation for enhancing muscle fibre numbers and postnatal growth, not all recent studies in pigs have been in full agreement. It is possible for some pig lines that females have been unwittingly selected for coping well with lower nutrition during pregnancy. However, less highly selected pig strains and other animal species, are likely to benefit from enhanced nutrition during pregnancy.