Inflammation – and in particular, CHRONIC inflammation – is a condition that will be reducing your profits by making your animals grow more slowly and less efficiently, will be draining the energy from your livestock, causing them discomfort and distress that no responsible farmer will want.

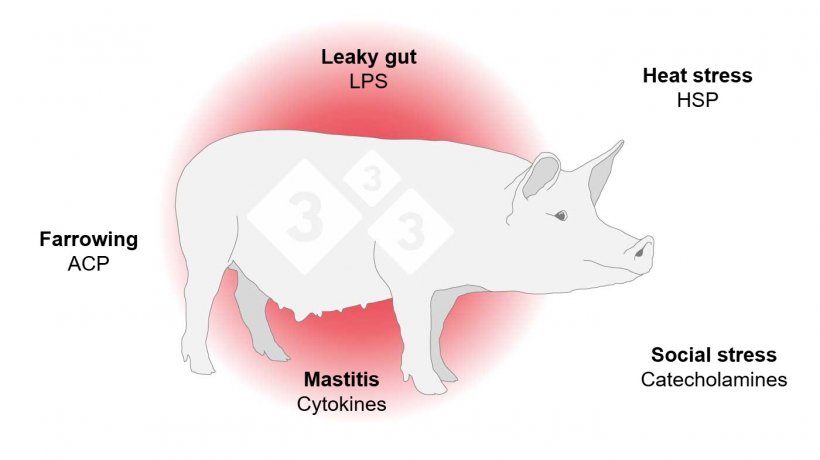

To be able to reduce or avoid such problems, we need to understand what the problem is. So, what is inflammation? According to the Cambridge Dictionary, it is defined as “a red, painful, and often swollen area in or on a part of your body1”. It is the physical sign that a body is reacting to a challenge, which might be physical (bruising, burns) or caused by an irritant (infections caused by bacteria, viruses; or allergens like pollen). Additionally – particularly in females – hormones can also initiate an inflammatory response. An episode of rapid acute inflammation is the bodies mechanism to eliminate such challenges, and so is an essential part of keeping the body safe and healthy.

However, when this rapid response does not “switch off”, we are then encountering chronic inflammation. Here, the defence mechanisms in the body continue to respond to a non-existent threat, and this itself causes large problems. In livestock, these problems are reduced production – lower growth, egg production, milk production, reproductive efficacy, and the overall efficiency that feed is converted to these products.

The reasons for this reduction in performance is due to the fact that chronic inflammation diverts nutrients – especially energy – away from production. One estimate is that chronic inflammation in fattening pigs consumes 85% of the amount of energy required for maintenance; so, NONE of this energy is available for growth (Kvidera et al, 2016; L. H. Baumgard, unpublished). In sows and cows, the energy diverted to chronic inflammation means less inter-uterine piglet / calf growth, with less milk produced and milk is of lower quality. All of these means pigs and other animals grow more slowly, younger animals do not develop as well and are more prone to disease challenges. For the sow / cow, increased energy demand means increased loss of body condition, shortening her lifespan and number of litters.

To combat this situation, we need to look more deeply into the mechanisms of inflammation, and what leads an acute response – essential for keeping a body safe and well – to change into a chronic condition.

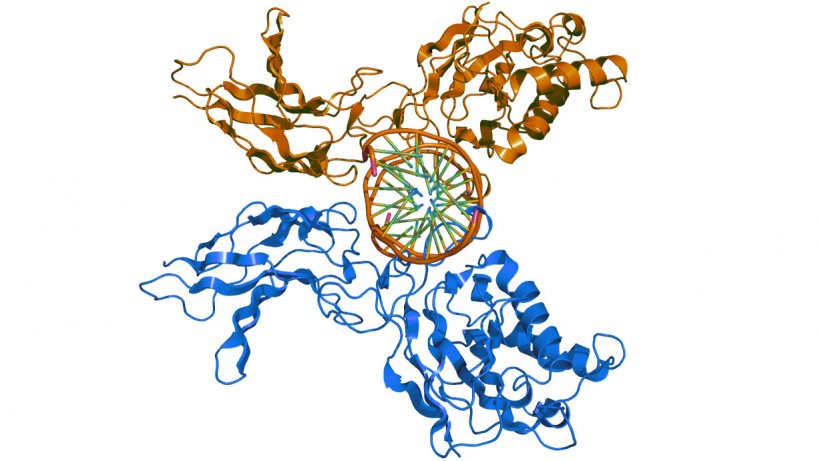

Inflammation is initiated in a well understood process. Once the body detects a challenge, a compound called Nuclear Factor kB (NFkB) starts the release of a variety of other chemicals called cytokines (Liu et al, 2017; Kogut et al, 2018; Dal Pont et al., 2023). These increase the width of capillaries in the affected area and also blood flow, speeding the arrival of white blood cells like neutrophils and macrophages that can consume pathogens or remove damaged tissue. The changes in capillaries and blood flow cause the reddening we see on our bodies.

This cascade of cytokines also triggers the production of the array of proteins involved in negating the challenge, including C-reactive and complement. These are produced in the liver, again using resources otherwise used for production. Additionally, a variety of different white blood cells – macrophages, neutrophils, and in particular lymphocytes, transition from virtually no metabolic activity to some of the most active cells in the body, as they replicate and start producing anti-pathogen compounds such as immunoglobulins (Guimaraes-Costa et al, 2012). Again, all of this activity requires substantial amounts of energy, amino acids and trace elements, reducing the quantity available for production.

If the challenge is successfully dealt with, the inflammation should then “switch off”. In fact, this termination process should start almost as soon as the initial inflammation begins (Sugimotos et al, 2016). But in many cases, it does not, leading to the wasteful chronic condition, where enormous quantities of the nutrients required for production (growth, eggs, milk, growing foetus) are all diverted to inflammatory response.

What is needed, therefore is a method to “block” the continued stimulation of the inflammatory response, to enable an acute phase to end and not become a chronic situation. Compounds that can inhibit the actions of NFkB would probably be useful – and this has been demonstrated in many animals. These compounds are to be found in some plant extracts… to be discussed in the next article “From Nature to Nutrition: New Insights to Address Chronic Inflammation in Swine”.