For most piglets in commercial farms, weaning means the abrupt separation from the sow, relocation to an unfamiliar pen, along with regrouping with unfamiliar piglets from other litters. This social stress is also accompanied by nutritional challenges as the piglet is transitioned from the sow’s milk to a plant-based diet – shifting from liquid to solid feed. These factors, along with other stressors, make weaning one of the most difficult periods in a pig’s production cycle. This phase is especially critical because piglet performance during this time directly impacts the economic success of swine farms. It is well known that the growth rate is dependent on sufficient nutrient intake.

However, in the first few days after weaning, feed intake often drops significantly, and some piglets may go a day or two without eating. As piglets fail to eat, they also fail to grow or even lose weight, which can delay development and affect lifetime performance. Given these challenges, management and nutritional interventions focus on encouraging piglets to eat as soon as possible to minimize growth delays and long-term performance losses. A deeper understanding of piglet feeding dynamics can help refine these interventions and better address the problem.

Health effects of weaning associated anorexia

The decline in feed intake immediately after weaning has significant consequences for piglet health and development. When piglets fail to consume adequate nutrients, their immune function is compromised, making them more susceptible to infections and diseases (Spreeuwenberg et al., 2001). Furthermore, the lack of passage of dietary nutrients in the intestine can cause disturbances in intestinal physiology of piglets such as degradation of the morphology and reduction in enzyme activity which ultimately results in lower nutrient absorption (Fàba et al., 2024; Moeser et al., 2017) that has repercussions in piglet performance. An unhealthy gut and increase in undigested nutrients often lead to post-weaning diarrhea—a common health challenge in commercial swine production. The combined effects of weaning stress and anorexia not only slow down piglet development but can also exacerbate long-term performance setbacks, including poorer feed efficiency and increased number of days to market weight (Boudry et al., 2004; Pulske et al., 1997).

When should the piglets eat

Weaning presents a physiological dilemma for piglets, as they are expected to start eating immediately despite being in a condition that is not conducive to feeding. Piglets must abruptly adapt from the highly palatable, biologically tailored sow’s milk to a man-made diet formulated based on assumptions about their nutritional needs using plant-based ingredients. Although the drop in feed intake in piglets post-weaning is common, the extent and duration of feed reduction vary widely among piglets, making it difficult to pinpoint a universal feeding pattern. Due to this, instead of trying to answer both when and how much piglets should eat simultaneously, it may be more prudent to focus first on when they should eat. While ensuring that the piglets eat enough to cover their needs, it is important to recognise the challenges piglets face during this transition and understand how they react to them and how it affects their feeding habits.

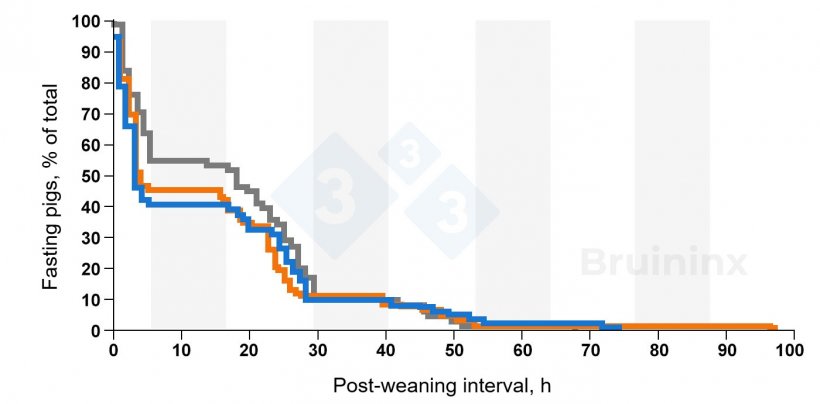

Bruininx et al. (2001) found that 10 hours after weaning, 40–55% of piglets had not yet eaten. Interestingly, a higher proportion of heavier piglets (55%) remained anorexic compared to smaller ones (40%) during this period (Figure 1).

However, by 24 hours, this difference between weaning weights disappeared, with only about 20% of piglets still not eating. By 48 hours, this number dropped to less than 5%. This temporary period of anorexia is often accepted in commercial farms, as the first 48 hours after weaning typically involve intense fighting among the new pen-mates as a new social hierarchy is established (McGlone, 1985). The peak of this fighting happens during the first few hours (Bruininx et al., 2001), which consequently dissuades the piglets from eating (Dong and Pulske, 2007). Le Dividich and Sève (2000) estimated that post-weaning energy intake during the first week is up to 40% lower than pre weaning levels. This reduction in energy and nutrient intake hinders growth, and piglets often experience weight loss in the first few days. This setback has long-lasting negative effect to the piglet’s performance. Research has shown that piglets that did not grow or even worse, lost weight, during the first week after weaning required an additional 10 days to reach market weight (Kats et al., 1992).

All these consequences shows that strategies to mitigate weaning associated anorexia are crucial. Proper weaning management such as gradual diet transitions and reducing environmental stress can help piglets adapt more smoothly and maintain optimal intestinal health during weaning.

Additionally, nutritional interventions, such as highly digestible diets, palatable feed additives, and gut health-promoting supplements, can encourage early feed intake. Feeding behaviour studies are also key to fully understanding the extent of the challenge and possible solutions.

Conclusion

Weaning has well-recognized negative effects on piglet metabolism, intestinal health, and immunity, many of which are linked to the significant drop in feed intake during this transition. A deeper understanding of the challenges piglets face, as well as the short- and long-term consequences of low feed intake, can help nutritionists formulate their diets to better support growth and improve health. By incorporating scientifically proven feed additives that enhance piglet feed intake and leveraging insights into piglet feeding behaviour, producers can implement more effective strategies to manage weaning stress and optimize piglet nutrition.