Current situation

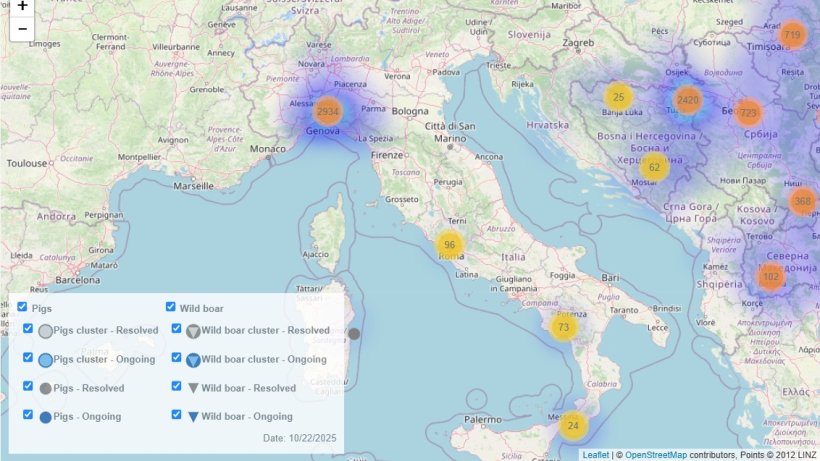

Northern Italy (Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and Tuscany) is the original epicenter and remains the most problematic area. After its introduction, the African swine fever (ASF) virus spread rapidly among the wild boar population, aided by the continuity of the habitat, high density, and complex terrain. The areas subject to restrictions have increased from an initial 1,000 km2 to over 21,000 km2 today. The twentyfold increase since 2022 demonstrates that the initial containment measures did not work as intended.

The Rome metropolitan area, where the disease was introduced in April 2022 due to human activity, represents a successful case of eradication. The closure of crossings under the Grande Raccordo Anulare ring road, combined with intensive passive surveillance and targeted depopulation carried out exclusively through traps, made it possible to eliminate the virus in a relatively short time (last case in summer 2023). Today, the capital is officially free of the disease.

In central and southern Italy (Campania, Basilicata, and Calabria), two independent introductions caused two outbreaks of limited extent without a substantial expansion of the restricted areas. Overall, the restricted areas cover approximately 5,000 km2, but the situation appears less complicated than in the north. In Campania and Basilicata, the surveillance system's low sensitivity does not allow the presence of the virus to be completely ruled out, while Calabria is now on its way to obtaining disease-free status.

In total, the areas affected now cover over 25,000 km2, with the North remaining the main problem to be managed and Rome an example of a successful strategy.

Photo 1. Map of ASF outbreaks.

Management basics

International experience has shown that managing ASF in wild boar requires a logical sequence of actions:

- Stopping the epidemic wave to prevent the spatial spread of the virus.

- Promoting the natural lethality of the virus, allowing the epidemic to drastically reduce the density of the infected population.

- Reducing the remaining population, once the virus has already caused a population collapse, to prevent a rapid resurgence.

These principles can only be effectively applied if supported by two key tools: functional fencing to limit the spread of the virus and widespread passive surveillance to monitor its evolution, identify the transition to the endemic phase, and certify eradication.

Photo 2. PIG BRIG - Innovative trap for wild boars by ISPRA.

What has worked and what hasn't

In northern Italy, the strategy implemented was inconsistent and fragmented. The fences were not completed on time, depopulation was done in a patchy and uncoordinated manner, and finally, surveillance detected far fewer carcasses than expected. In many cases, positive reports came from citizens rather than from structured search systems.

In Rome, on the other hand, the consistent implementation of the recommended measures demonstrated that a timely and unified approach can work. A clear chain of command, inter-institutional cooperation, and transparent communication made rapid eradication possible.

In central and southern Italy, measures have been more gradual, cautious, and consistently applied. Although the absence of new positive cases is encouraging, the surveillance system still needs to be strengthened to confirm that the virus has truly been eradicated in Campania and Basilicata.

A transversal problem, which has been felt in all areas, is the fragmentation of responsibilities. Regional decisions have not always been aligned with the national strategy, leading to delays and inconsistencies. Local resistance to fencing or the suspension of hunting has often slowed down essential interventions.

Lessons and outlook

The future of the fight against ASF in Italy depends on the ability to build a unified vision that clearly distinguishes between the management of the virus in wild boar and domestic pigs.

In the livestock sector, the priorities—biosecurity, controls, and surveillance—are now shared. In wild boars, however, the approach remains more inconsistent and reactive.

To improve, Italy will need to:

- Define a clear national strategy, shared by all levels of government;

- Invest in passive surveillance and risk communication, essential tools for engaging stakeholders, hunters, and citizens; and

- Maintain consistency and continuity in decision-making, avoiding fluctuations due to local pressures or social perceptions.

The most effective experiences—such as Rome's—show that when actions are swift, coordinated, and clearly communicated, it is possible to eradicate the virus.