Paper

Holtkamp DJ, Yeske PE, Polson DD, Melody JL, Philips RC. A prospective study evaluating duration of swine breeding herd PRRS virus-free status and its relationship with measured risk. Prev Vet Med. 2010 Sep 1;96(3-4):186-93. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.06.016.

Paper summary

What are they studying?

They evaluated the AASV PRRS Risk Assessment tool (for Breeding Herds) to determine or establish how long a farrow-to-wean breeding herd would maintain its virus-free status. The main biosecurity risk factors related to PRRSV infections in breeding herds were also evaluated.

How is it done?

33 farrow-to-wean PRRS-virus free swine breeding herd sites were followed, recording if (and when) the farms became infected by PRRS-virus. The PRRS-free status was established by either populating a new site with virus-free breeding animals or by completely depopulating the site and repopulating with PRRS virus-free breeding animals.

During the 452 weeks of the study, the effect of the season and the method by which the site was established free of the PRRS virus, as well as internal and external risk scores measured by the PRRS Risk Assessment tool, were evaluated.

What are the results?

85% of the farms (n=28) became PRRS positive during the study, and 40% turned positive during the 1st year after they were established free of PRRS virus.

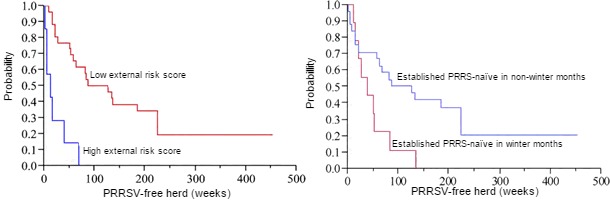

Having higher external risk scores was associated with a greater and earlier risk of becoming positive for the PRRS virus. On the other hand, the internal risk score was not significantly associated with turning PRRS-positive. Establishing PRRV-free breeding herd sites in the winter months (November through February) was associated with a greater risk of becoming positive for the PRRS virus compared to those established in non-winter months (Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2. Breeding herd site probability to remain free of PRRS virus depending on the risk score and the season when the site was stablished PRRS virus-free.

The association between the risk of becoming positive to the PRRS virus and the external risk score was confounded by the method used to establish the PRRS virus-free status.

What implications does this paper have?

The swine industry needs better methods to measure and quantify disease related risks as a first step toward development of good, epidemiology-based prediction rules.

This study supports the value of the PRRS Risk Assessment for the Breeding Herd tool for evaluating whether sites will remain free of the PRRS virus long enough to recover the costs of eliminating the virus.

It could also help in developing and executing regional elimination projects by enabling the monitoring of risks associated with PRRS virus-free herds in the project area becoming positive.

|

Those farmers whose farms are located in areas of high pig density know how difficult it is to maintain stability when it comes to PRRS. Infection control is difficult once the infection has reached the farm, but not impossible. Implementing the corrective actions already discussed in previous articles of this series —immunization, hot spots control, management etc.— will allow the farm to regain stability and return to production levels similar to those achieved by negative farms. However, one of the concerns in these areas (and the rest of them) is how to prevent new introductions of PRRS virus re-altering the stability achieved. The solution is, theoretically, easy, and it involves implementing sound external biosecurity measures. The article clearly shows that those farms with a higher level of external biosecurity are the ones with longer periods of negativity. But how do we improve biosecurity?? One of the first things to do in order to achieve an improvement in every area, is to compare ourselves to the rest of the community. We do it when we want to improve productivity or production costs. In this case, we do not only compare ourselves to those close to us (local or national level), but also to those in other world regions, as we are all aware that we compete on a global level. But when we talk about improving biosafety, how can we compare ourselves? The idea this article suggests, ie measuring external risks, could be very interesting as it allows us to compare holdings based on a numerical figure, and thus initiate corrective measures to improve and numerically verify the improvements achieved. In areas of high density of pig farms, implementation of regional plans to reduce the risk of new introductions is considered essential to achieve better control of PRRS. These regional plans consist of using existing health protection organisations as a tool to enable implementation of these joint actions. These joint actions would include: Centralized management of information (outbreak reporting, virus sequencing to track outbreaks); implementation of common prophylactic plans; actions on animal movement (restriction on sources of replacements or piglets); and of course biosecurity monitoring, since, as the article shows, it can be a useful tool to improve health of both farms and the area concerned. |