Introduction

This is a farm with a conventional health status (PRRS +, ADV -), located in a Spanish region with a high swine density. The sows are vaccinated against parvovirus / erysipelas (cyclic vaccination) and against ADV and PRRS (live vaccine, blanket vaccination) every 4 months.

The farm always had bad results in the breeding area, with high percentages of returns-to-oestrus and empty sows when checked by ultrasound. In October 2009 they tried to improve this situation by organizing the farm in 2/3-week batches and weaning at 28 days, and receiving semen from a boar stud. The reproduction results improved significantly, with the majority of the batches exceeding a farrowing rate of 90%.

As of February 2010, the farrowing rate went worse in the successive batches, reaching a rate of 82%, and the percentage of sows with a negative pregnancy ultrasound test rose up to approximately 5%. At the same time, the number of sows with delayed oestruses after weaning increased.

The farm was visited in August 2010 and an analysis of the returns-to-oestrus during the previous 8 months was carried out in order to try to solve the problem.

| Parity | % Returns | Farrowing rate (%) | Total | Goal | Annual average | ||

| 1 | 9.3 | 85.8 | No. of returns (TR) | 174 | < 10 % | 11.5 % | |

| 2 | 17.3 | 81.3 | Total cyclic returns (TCR) | 97 | < 6 % | 6.4 % | |

| 3 | 15.6 | 76.1 | Cyclic returns 1 (CR1) | 73 | 4.8 % | ||

| 4 | 6.1 | 85.7 | Cyclic returns 2 (CR2) | 24 | 1.6 % | ||

| 5 | 8.9 | 82.2 | CR2/TR | < 10 % | 24.7 % | ||

| 6 | 4.5 | 79.5 | Total acyclic returns (TAR) | 55 | < 4 % | 3.6 % | |

| 7 | 0 | 84.8 | Acyclic returns 1 (AR1) | 32 | 2.1 % | ||

| 8 | 0 | 80.0 | Acyclic returns 2 (AR2) | 23 | 1.5 % | ||

| 9 | 0 | 66.7 | TAR/TR | < 30 to 35 % | 31.6 % | ||

| AR2/TAR | < 30 % | 41.8 % | |||||

| Early returns | 8 | < 0.5 % | 0.5 % | ||||

| Late returns | 8 | < 0.5 % | 0.5 % | ||||

| Empty sows | 6 | < 0.5 % | 0.4 % | ||||

| Empty sows ≥ 60d: abortions | 2 | ||||||

| Empty sows ≥ 60d: returns | 4 |

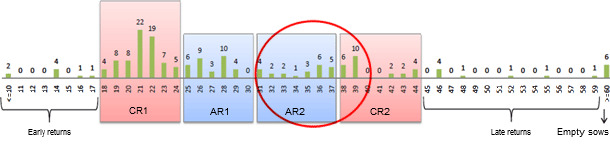

Figure 1. Analysis of the returns-to-oestrus from February to August 2010.

Analysis of the returns-to-oestrus during the previous months

- The total percentage of returns-to-oestrus is excessive: 11.5 %.

- The farrowing rates are low, but they do not change excessively between parities. The results are worse in 2nd parity sows (attributable to the second farrowing syndrome), and especially in the 3rd parity, which is difficult to justify.

- There is an unusual increase of the returns-to-oestrus at 31-39 days. The majority happened in sows that had been previously negative to the pregnancy ultrasound test and did not appear before 42 days (mainly between 36 and 39 days).

Main conclusions of the analysis of the returns-to-oestrus

A high percentage of the returns-to-oestrus (between 31 and 39 days) is difficult to explain. There would be two explanations to justify them:

Option 1: That these sows were losing their gestation at 25-35 days. Nevertheless this would not fit in well, because if this had happened they should have been positive to the pregnancy ultrasound testing carried at about 25 days of gestation. Also, the majority of the sows with a positive pregnancy ultrasound testing do not lose their gestation subsequently.

Option 2: That some of the sows were not really in heat when inseminated and that their real heat was not detected ('return-to-oestrus' at between 7 and 18 days after the insemination) in the majority of them. This would also explain the 0.5% of the early returns-to-oestrus (before 18 days). The result would be a 'return-to-oestrus' between 28 and 39 days, after having been negative to the pregnancy ultrasound testing, and this is just what we see in the analysis of the returns-to-oestrus (Fig. 1).

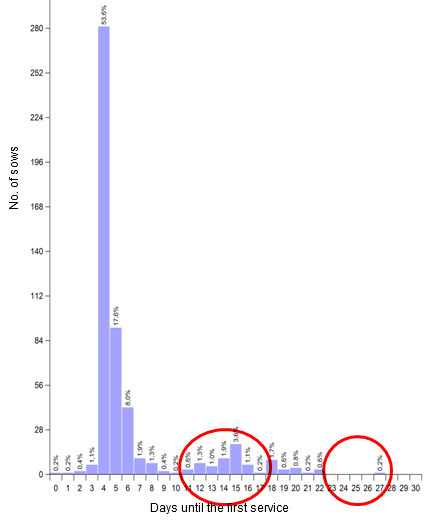

An analysis of the days after the weaning on which the sows are inseminated (Fig. 2) shows that almost no sows come into heat at about 25 days, when this should happen in those sows that have not been identified as having a normal heat after their weaning.

Figure 2. Days to first service after weaning histogram (from February 1st 2010 to August 1st 2011)

We also see a delay in the coming into heat, with a peak between 12 and 18 days after weaning (some 12% of the weaned sows). Nevertheless, there are not too many heats between 7 and 11 days after weaning, that would be the moment in which those sows with a delayed oestrus would be starting to come into heat (due, for instance, to a bad body condition after weaning).

This leads us to think that maybe a high percentage of sows are coming into heat during the last week of their lactation (the weaning is at 28 days). The hypothesis is that some of those sows would be inseminated incorrectly after their weaning.

This hypothesis would be supported by the following facts:

- Most of the sows that are negative to the pregnancy ultrasound testing are the ones inseminated 4 days after their weaning (Monday).

- The rest of the days, there are less mistakes (returns-oestrus), in general, and less sows that are negative to the pregnancy ultrasound testing, in particular.

- There is a high percentage of sows with a delayed coming into heat. These sows are the ones inseminated between batches, because the gilts are included in the insemination week by using altrenogest. Surprisingly these inseminations are the ones that yield the best results.

This happens in the majority of the batches and is aggravated as of September.

The semen does not seem to play an important role, because it is received daily (except on Thursdays and weekends) from a boar stud. These facts still reinforce even more the theory that some sows (especially those on Mondays after their insemination) are being inseminated without showing heat signs due to errors in the heat checking and probably to the hurry for inseminating the sows as soon as possible after their weaning.

One of the possibilities for verifying this hypothesis would be to identify the sows that are in heat during their lactation by means of a postweaning ultrasound testing (ovaries in their luteal stage would be seen, with an homogeneous image that is typical of that period) or watching at the ovaries of culled sows after their weaning. In this case, a progesterone analysis was carried out from blood samples taken from newly weaned sows. The 58 weaned sows were sampled on November 25th without the farmers knowing it. Fourteen of them (some 24% of the weaned batch) showed high progesterone levels, and this suggests that they were in their luteal phase and ovulated during their lactation.

Table 1. Progesterone levels in 58 weaned sows.

| Progesterone levels (ng/ml) | Number of sows | |

| Follicular growth and ovulation | +/- 0.5 ng/ml | 44 |

| 3rd-4th oestrus cycle day | 3 – 5 ng/ml | 5 |

| 7th-8th oestrus cycle day | +/- 15 ng/ml | 9 |

| 14th-15th oestrus cycle day | +/- 30 ng/ml | 0 |

Four of the 14 sows were inseminated on Monday 29th and one on Tuesday 30th November. Obviously, they ended up being negative to their pregnancy ultrasound testing. Convincing the farmer that the problem was on the oestrus detection was not easy. During the months of November, December, January and February the results were especially bad, this coinciding with the colder and shorter days season. Curiously enough, when the sows entered the season in which they should be showing the best results, in this farm exactly the opposite happened. The reason was not a loss of the pregnancy, but the fact that the sows 'came into heat too well'. They came into heat so well, that a high percentage of them (up to a 25%) did so during their lactation. The problem was that after, the oestrus detection was bad, and due to the hurry some of them were inseminated without being in heat.

Since March the results began to improve, probably due to the changes implemented in the oestrus detection standard. In April the results improved spectacularly, coinciding with a better coming into heat of the sows.

Why do the sows come into heat during their lactation?

Some lactating sows show LH peaks that are similar to those seen in the weaned sows.

If there are also factors that affect the quality of the stimulus of the piglets during the lactation as, for instance, small litters, small or unviable piglets, litters with diarrhoea, changes in the litters when using foster sows, etc., the situation becomes aggravated. We must keep in mind that in our case, the sows in their third parity were the ones that showed the worst results (curiously enough these are the sows mainly used as foster sows).

Mycotoxins, especially the ergotoxins produced by Claviceps purpurea can give rise to a prolactin suppression that favours the coming into heat during the lactation so, although it was not carried out in this case, it would have been interesting to control their levels in the feed.

The high feeding levels during all the lactation (especially during the colder time of the year) added to the short photoperiod effect (that stimulates the melatonin levels) are very important causes of the coming into heat. This is the reason why the results worsened during the colder months.

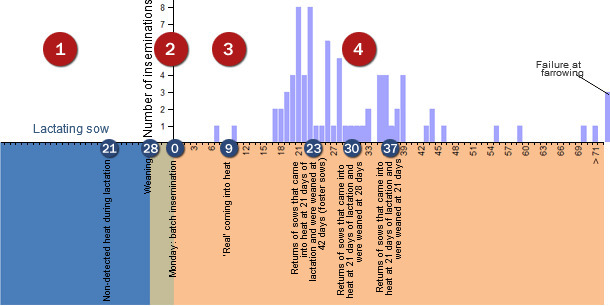

Figure 3. Analysis of the returns-to-oestrus during the troublesome period.

79 sows returned to oestrus between Sept 1st 2011 and March 1st 2011 (average of days at return-to-oestrus: 33.6 days)

Looking retrospectively to the distribution of the returns-to-oestrus during the most troublesome period (from September to March), we understand what was happening:

1. A high percentage of sows were coming into heat at 21-28 days of lactation.

2. Some of these sows were wrongly inseminated, especially during Mondays of the inseminations week.

3. The normal coming into heat of these sows would happen around day 14 after their weaning, but if they were inseminated they returned to oestrus about 10 days after their service.

4. Nevertheless, very few of these returns-to-oestrus were detected because the coming into heat was not controlled correctly during those days. This gave as a result sows that were negative to the pregnancy ultrasound test, and returns to oestrus as of the 25th-26th day of gestation, but before the 42nd day of pregnancy. It is important to highlight that even the peak in the returns-to-oestrus seen around the 27th day could be justified due to this problem. Even some of the returns-to-oestrus around the 23rd day could be due to the sows coming into heat around the 21st day of lactation, because they are weaned at 42 days (for example when being used as foster sows).

Conclusion

The quality of the oestrus detection still is, in many cases, the main cause of the returns-to-oestrus on the farms. When this happens, the acyclic returns normally increase, without this meaning that there are problems related with the loss of pregnancies. In these cases, the interpretations of the analyses of the returns-to-oestrus must be taken with great caution. An analysis of the results by day of the week can be of great help for guiding the diagnosis.

The coming into heat of the sows during their lactation is a problem that is on the rise, and that is probably due to the high intakes that are being obtained, added to the fact that the high prolificacy forces us to make lots of changes in the litters and obtain foster sows that may end up causing a premature coming into heat. It is not necessary to interrupt the lactation in these cases. An analysis of the weaning-to-service interval may help us to see if this is happening on our farms.